I Want to Buy Queer Art for My Home, Even If I Don't Exactly Know Why

There's a sudden yearning to fill my walls with art from queer artists that wasn't there before. Understanding its source might just help me find the right pieces for my collection

I ’m in the market for some gay art. My partner feels the want for it, too, but we have put it off, wary of becoming the cliché: thirty-something gay men with a Tom of Finland book on the coffee table and a line drawing of an appendageless male torso hanging over the fireplace. It’s the basic starter pack of cis-gay domesticity. To succumb feels at once predictable and, somehow, too inevitable.

The trouble, I’ve realized, is that my idea of queer art — what it is, what it means — is limited. Somewhat of a blunt instrument. Still, it’s not entirely my fault. There’s a recurring convergence of styles and themes persuasive enough to suggest, if not a singular queer aesthetic, then at least its shadow.

What is that queer aesthetic? It’s one of the first questions I ask Davy Pittoors, a queer independent curator and arts organizer, based in Rye. “I get asked that question a lot, and I really hate it,” he tells me. We’re off to a good start.

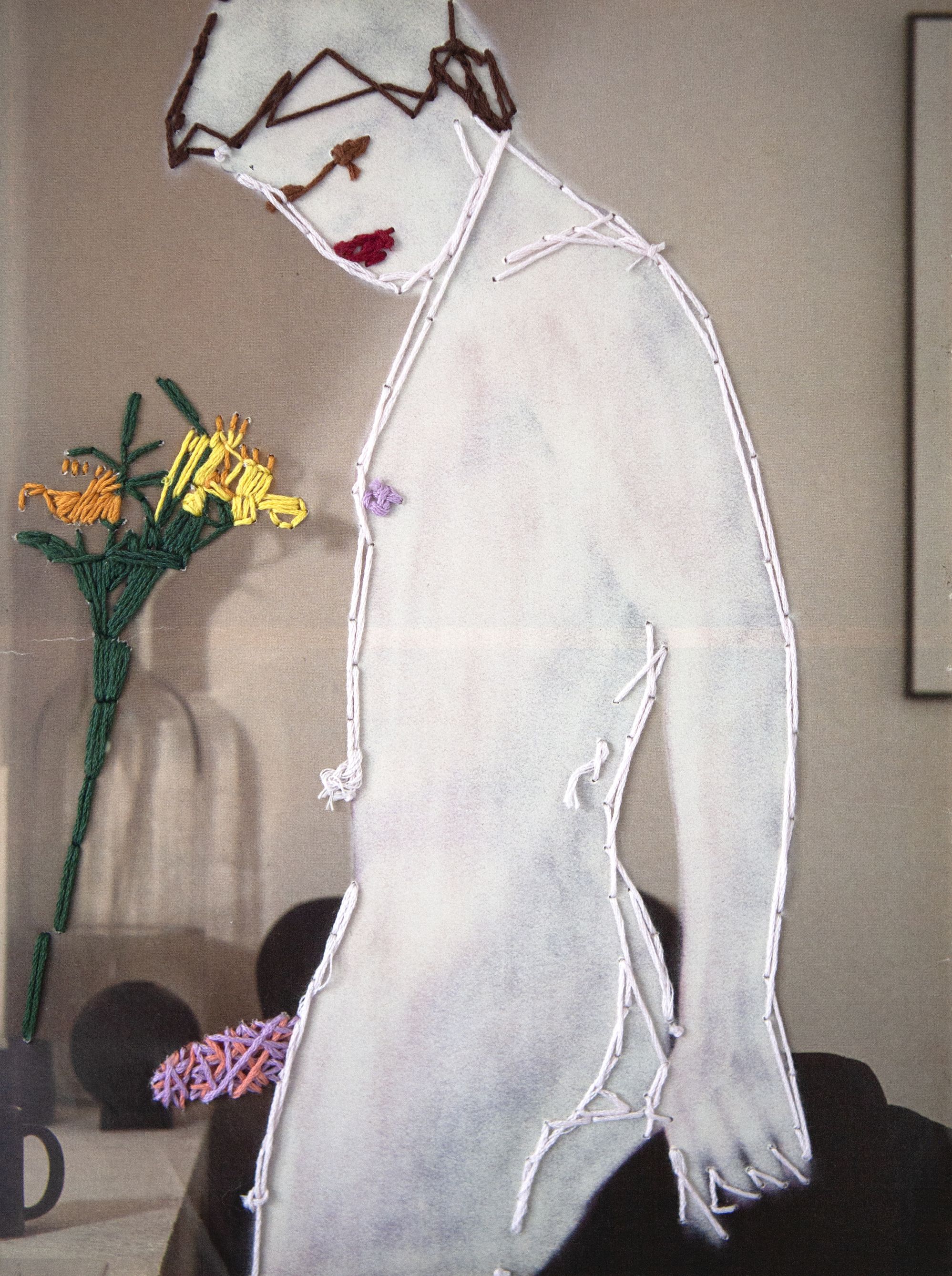

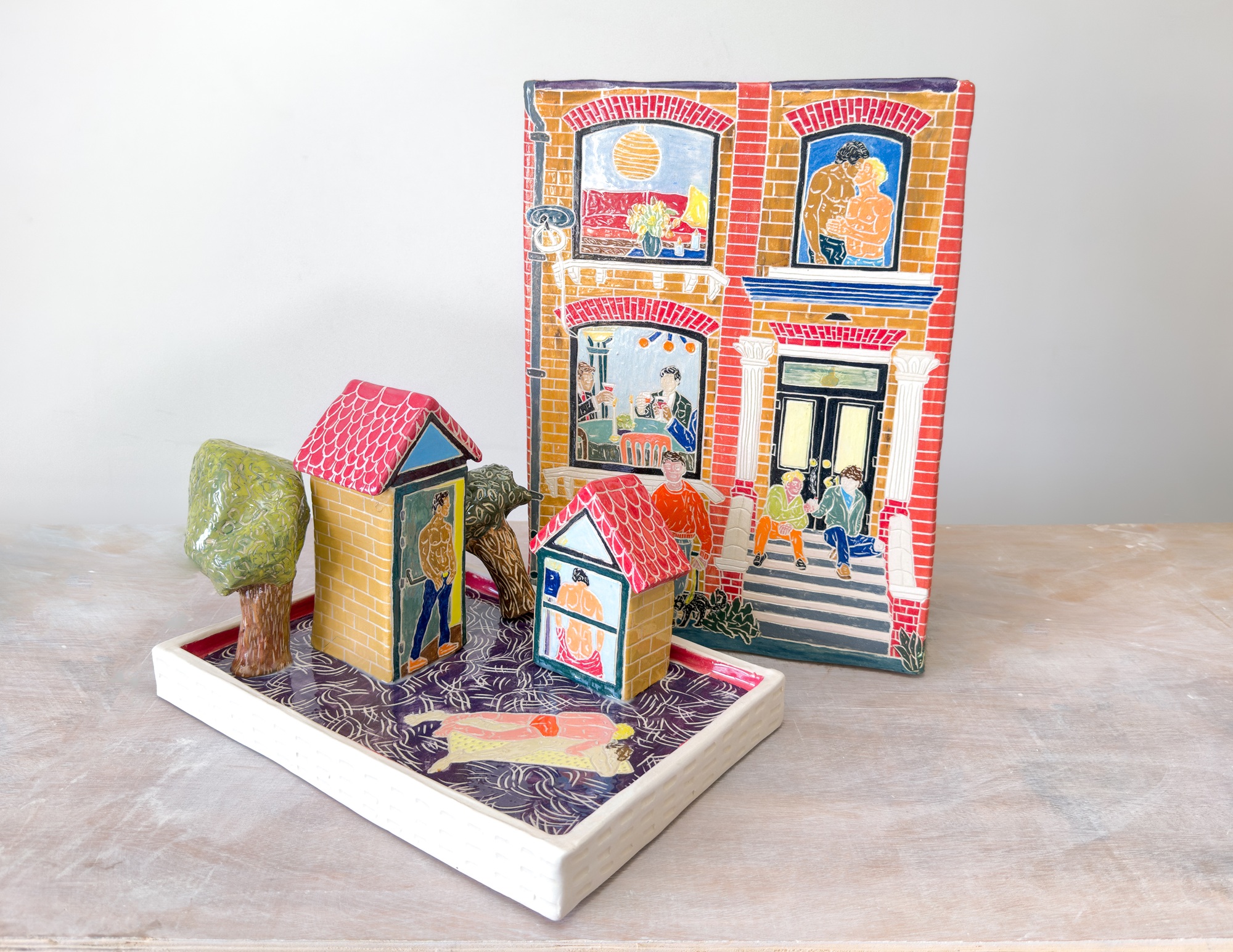

I first stumbled across Davy on Instagram several years ago, when he was running a small queer art shop and gallery in Margate — a smart, beautifully presented curation of artworks and ephemera by queer artists, from vintage magazines to watercolors to Grecian-style ceramics decorated with risque gay frescoes.

These pieces resonated with me in ways that went beyond my previous encounters with queer art, though I couldn’t quite explain why. As an interiors editor, I’m predictably invested in how my home looks, but this longing to see my queerness reflected in it felt harder to place. “Anything we buy or create is actually a form of self-expression,” Davy tells me, “and I’m fascinated by that. I think queer people, including myself, often don't feel that at home in the world, so tend to be very intentional about those choices.”

Davy tells me that it’s something that has manifested itself more so in his home than the clothes he wears, and with a wardrobe stuffed with monochromatic basics myself, I can relate. “For me, creating a home is really important, and it's how I express my identity,” he says.

Davy is the curator behind Queeriosities, an annual art fair and design exhibition in London in its third year, opening today — the biggest in the UK, and a new cultural touchpoint for the city’s LGBTQIA+ arts community and its collectors. And, I suppose, would-be collectors, such as myself.

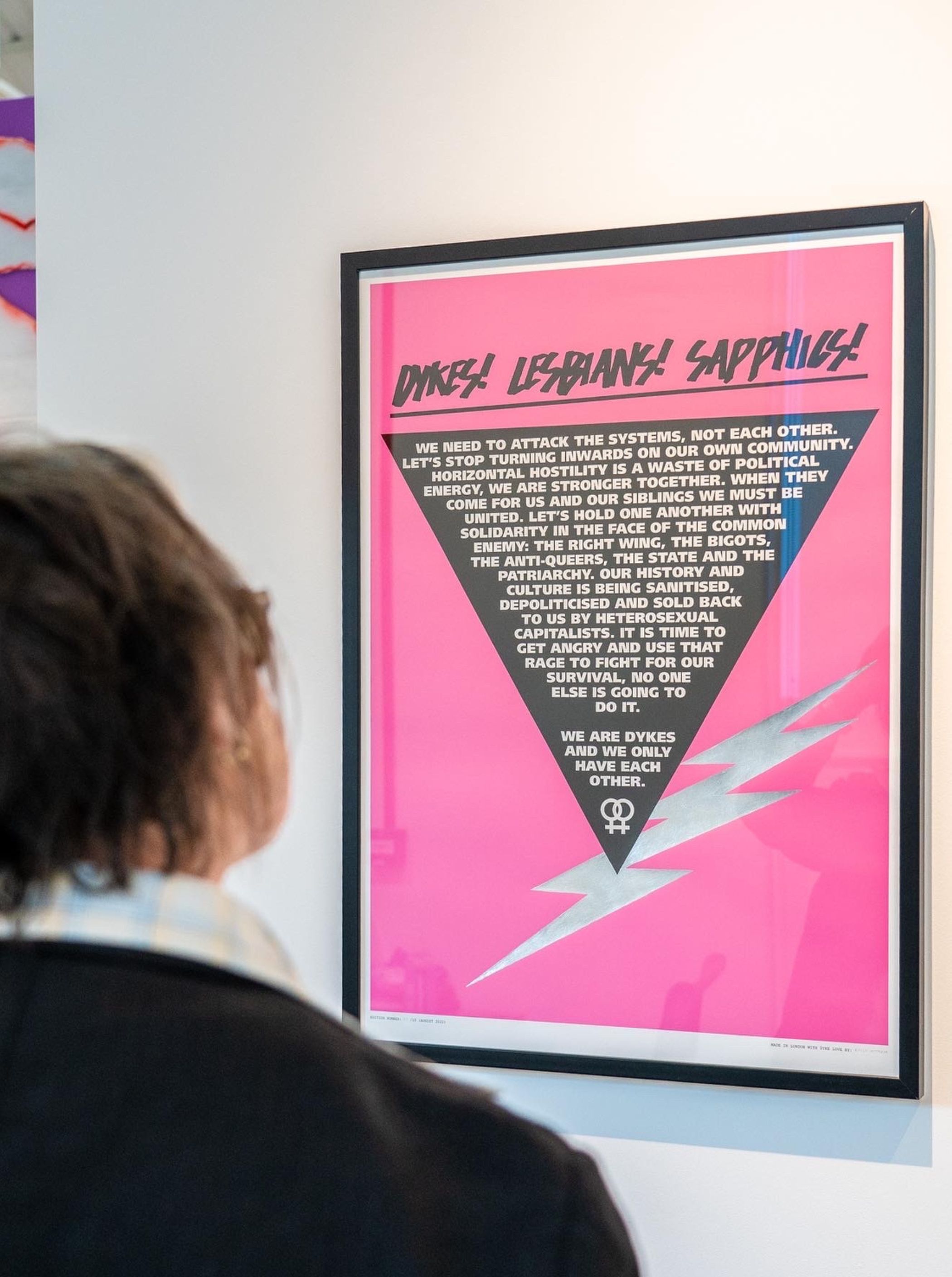

And yes, you’ll likely see some of those motifs I’ve noticed commonly in queer art — sex, kitsch, activism, joy, even tragedy — but it’s not what defines the artists featured in the exhibition, says Davy. “I think they're all tools that the queer community has learned to wield throughout history, but I don't think they define queerness in itself — not any more than a hammer defines a house. Queerness resists definition, and the fact that it is so ‘slippery’ is what makes it beautiful, what makes it strong, and makes it constantly evolving.”

It’s easy to be drawn to art that wears its queer identity openly, but in reality, it exists in all shades of subtlety. I think of an exhibition at Charleston this September, part of its ‘Queer Bloomsbury’ celebration, where Bloomsbury Group artist Duncan Grant’s erotic drawings were on display. They’re undeniably demonstrative of his queerness, but as head of collections, research and exhibitions at Charleston Darren Clarke tells me: “You can look at everything he makes as queer, but, even in the erotic drawings, the use of line, color, form, shape, and composition is the same as when painting a portrait of his mum or a bowl of flowers. The subject matter is almost incidental.”

The more interesting part is, possibly, the story. “There was a lot of gift exchange, for example,” says Darren. “We have a little jigsaw puzzle that Duncan Grant made for his friend, Saxon Sidney Turner, and it's of a naked bear, a pair of buttocks, which are sort of red and glowing from being spanked — Saxon had a particular interest in that sort of activity.” Its requirement to be kept secret meant that it was art to be enjoyed, not so much for commercial merit, and Darren even has a theory that the collection of erotic drawings became grouped as Duncan Grant was preparing for a Tate exhibition in 1958. “He had curators from the Tate coming around to his place in London, looking through piles of artwork from the previous decades, and I believe he didn't want them to see these.”

I had always sort of imagined Charleston as being a space of unbridled creative freedom and queer community, but as Darren points out: “When Duncan and his partner David Garnett were forced into rural Sussex to escape conscription, they were actually losing some of their freedom in London. If you want your queerness in the countryside, you sort of have to take it with you.”

Having left behind the more metropolitan days of my youth for a quieter town outside of London, the remark hits home. It recalls a conversation with Russell Whitehead, one half of interior design studio 2LG Studio, co-founded with husband Jordan Cluroe. The couple recently moved from a four-bedroom Victorian townhouse in Forest Hill to a one-bedroom in Shoreditch.

“As children who were told you’re not going to get married (as gay marriage wasn’t legal then), I think we went out into the world looking for the perfect family home to prove the naysayers we were allowed to have that, too,” Russell tells me. “It was important for us to get the four-bedroom Victorian home, and we spent our blood, sweat, and tears, and every hour we had to try and make that happen.”

“Then, when we sat in the house and we realized that our day-to-day life was just us — we had these guest rooms for family to come, but we wondered: who did we get this house for? Do we need these extra bedrooms?” This led to further questions: “What would our queer home be? Where would it be?”

Russell and Jordan’s questioning led them to imagine what their “queer dream house” looked like, prioritizing the things that mattered to them. Some of it is still about aesthetics — including “a whole floor that will be like a live-in shop for Jordan’s collection of clothes that just happens to have a bed in it” — but it’s now more about place, rhythm, and community. “I just want to be surrounded by creative queer people,” Russell says.

They put that ethos into action with their recurring London Design Festival exhibition, You Can Sit With Us, which, this year, they devoted entirely to queer artists and designers. “Partly, this was because we had realized there were so few people in the furniture and lighting industry who identified as queer,” Russell says. “It's sort of relatively easy to find artists or ceramicists in that arena, but the furniture world, specifically, is incredibly heteronormative and largely male. One way around that was to kind of work with people from multidisciplines and ask them to do things that they hadn't done before, but we also reached out to people we know in the queer community and asked them, ‘Do you have any friends?’”

The act of community-building is a recurring theme that, more than subject matter, seems to be the common link. At La Camionera, a lesbian bar in London's Hackney that opened earlier this year, all the artwork adorning the walls comes from friends of co-founders Clara Solis and Alex Loveless. “We have pieces by friends that are regulars at the bar, like Rene Matic, and Faye Wei Wei,” Alex tells me, “while curator Tosia Leniarska also sourced us some amazing pieces.”

There’s a subtle charm to La Camionera’s collection — a wink, if you will — reflecting the IFYKYK vibe of its name (La Camionera means ‘female truck driver’ in Spanish, slang for a butch lesbian). Designed by Studio Popelo and Wet Studio, the space doesn’t announce its queerness as loudly as some of London’s more infamous scene spots — the city’s most famous gay bar is called G-A-Y, after all — but the signs are there if you look. On one wall, a painting depicting a woman in a crop top wielding a power drill, for example, feels like a knowing nod. “The artists are just people we know that make great work, and there’s nothing to really give away the identity apart from one brilliantly-lesbian photograph by Jill Posener — and we’ve even thought about moving that when we have our parents’ and kids’ coffee mornings,” Alex adds.

Something is interesting about the subtlety of queer spaces like this, especially in contrast rainbow flag–studded spectacle of pride parades. Or take, for example, another recent opening, Roses of Elagabalus, a queer members club named after a painting by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema depicting a young trans emperor, which draws on the illicit queer clubs of history — from burlesque dens to gay bathhouses — and that has a ‘no phones’ policy. These are places of belonging, but also public spaces, where that sense of safety needs to be assured and protected.

It’s likely not new news to you that not only are queer people under scrutiny and attack, but queer art is, too, especially as it relates to trans and gender non-conforming people. In the States, Donald Trump rescinded federal funding for art that ‘promotes gender ideology’ this year, while controversy over a depiction of the Statue of Liberty as a black, trans woman placed artist Amy Sherald at the ‘heart of a culture war’ — one that rages just as fiercely this side of the Atlantic.

As Davy says: “Queer artists and craftspeople are some of the bravest and most resilient members of the community, because the anxiety of living and working in these times can become exhausting. I have seen some artists double down on their work to make sure that their viewpoints and their voices aren't lost. And others feel they need to step away from their work and dedicate themselves completely to activism.”

Through Queeriosites, Davy’s also created a safe space for queer artists to showcase their work beyond those anxieties, without fear of censorship, or even as simple a microaggression as someone ‘raising an eyebrow’ to their work. In an exhibition filled with queer artists, no one, really, has to come out.

"There’s the sense of an exhale that I experience when everyone's in the room,” Davy says. “We can actually leave all this baggage at the door, and we can just focus on being ourselves and just showing the work we want to show.” That sense of community, then, doesn’t just run through the artists exhibiting, but the patrons attending, too. We all know what we’re there for.

I ask Russell, of 2LG Studio, from where he thinks that yearning to invest in queer art comes. “It's highly likely that you're going to respond to the output of a queer artist because you might connect on specific wounds that you've been given,” he says, “but I also think there's an element of wanting to put your dollar into the community that you live in, whether you actually live in it, or feel your part in it.”

That may be where my home life is missing right now. I don’t live in a town with a particularly rich queer culture, but I feel that through filling my house with the work of queer artists, I’m bringing the ‘queerness to the countryside.’ In my own home, I can create some sense of queer community, even if it’s one-sided, curated on my part — with the added bonus of supporting events like Queeriosities, where I can go and still soak up the real thing.

Further Reading

Want more perspective on queer arts? I asked Davy for his further reading list:

● "LDN Queer Mart is another London-based fair that does a great job platforming emerging and diverse queer voices. I really love what they put together and they do it really thoughtfully.

● The Museum of Transology recently held its 10-year retrospective, Trancestry, and it was masterful. The work that they’ve done creating such an amazing archive of objects and stories — and bringing communities together — is beyond important.

● On the notion of home, the Do Ho Suh Genesis exhibition at the Tate is a really incredible deep-dive into the idea of home, how we carry it with us and the ways in which it shapes our memories and experiences.

● Charleston in Lewes and Firle, Prospect Cottage in Dungeness, the Dennis Severs House in Spitalfields and the multiple points of queer history from Radcliffe Hall to Edward J. Burra and Henry James here in Rye are all constant sources of inspiration for me.

● A few key books: The Queerness of Home by Stephen Vider, Crafted with Pride by Daniel Fountain, Buying Gay by David K. Johnson — and, of course, Gemma Rolls-Bentley’s Queer Art."

Hugh is Livingetc.com’s editor. With 8 years in the interiors industry under his belt, he has the nose for what people want to know about re-decorating their homes. He prides himself as an expert trend forecaster, visiting design fairs, showrooms and keeping an eye out for emerging designers to hone his eye. He joined Livingetc back in 2022 as a content editor, as a long-time reader of the print magazine, before becoming its online editor. Hugh has previously spent time as an editor for a kitchen and bathroom magazine, and has written for “hands-on” home brands such as Homebuilding & Renovating and Grand Designs magazine, so his knowledge of what it takes to create a home goes beyond the surface, too. Though not a trained interior designer, Hugh has cut his design teeth by managing several major interior design projects to date, each for private clients. He's also a keen DIYer — he's done everything from laying his own patio and building an integrated cooker hood from scratch, to undertaking plenty of creative IKEA hacks to help achieve the luxurious look he loves in design, when his budget doesn't always stretch that far.