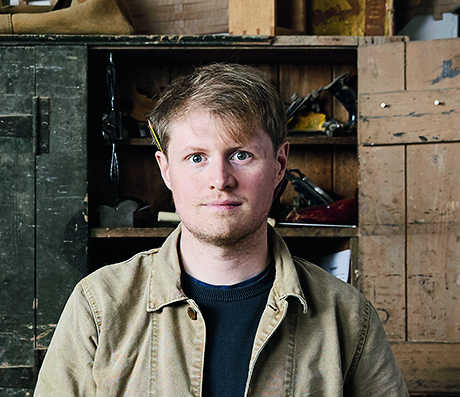

Why you should join the no dig movement - designer Sebastian Cox makes an impassioned plea

Sebastian Cox is a big believer in no dig gardening, and here he explains why you should drop your forks and join up too

The Livingetc newsletters are your inside source for what’s shaping interiors now - and what’s next. Discover trend forecasts, smart style ideas, and curated shopping inspiration that brings design to life. Subscribe today and stay ahead of the curve.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Much has been made of the no dig gardening movement lately. It's said to be better for the environment, better for the soil, better for your back, better all round. Here, designer Sebastian Cox explains why you should be joining the no dig revolution.

When I see a tractor ploughing in the spring I’m stirred by memories of running behind my dad across a downland field of fresh flint and clay. He’s known for his forthright pace on hard ground, and I can’t think of many people who could traverse a ploughed field faster than him on foot. In my childhood memory he’s effortlessly striding from furrow to furrow and ten year old me is running up and down each trench with energy-sapping sticky boots, trying to match his pace as we walk across the farm. I’m aware, in the memory and present, that we could be any father and son for a thousand years in that place, at that time of year.

Whether I will replicate this seemingly timeless experience with my children, both under two, is unknown. The way we’re treating our soils, we’re learning, is bad. Will we still plough later in this century?

Turning the soil ready for crops feels as natural as the germination of the seeds we sow. There are no chemicals involved in a day’s ploughing, and a plough is firmly rooted in the 'old ways’, having changed little in design since they were drawn by horse, so how can it possibly be malign? It seems until very recently we have failed to study and understand the earth beneath our feet and the life it holds. As we study and learn, we realise the degradation we’ve been imposing.

My dad hasn’t farmed for years, but told me last winter to his horror he’d learned that the unique smell which comes only from a ploughed field is the smell of carbon dioxide escaping the soil as broken-up organisms release it. Soil health wasn’t taught at his agricultural college.

My childhood ploughing memory also bears evidence of change. Earlier this spring, on seeing a plough turning the dark soils of my new home in Thanet, I was struck by the half dozen seagulls following it. My childhood view sees murmuration-density gulls, corvids and other scavengers as the tractor turns another annual crop rotation on our small farm. The number of birds behind the plough is determined by the amount of edible life the turned soil offers. Our modern soils, tilled and over-worked, it seems, contain less life. Of course, ploughing isn’t the only culprit, but it’s currently and rightly on trial alongside chemical fertilisers and ‘cides. The UN warns we only have 60 harvests left if we keep farming as we do.

If we think of soil as biology - a network of connected living organisms - we realise that breaking it up is harmful to that complex ecosystem

Sebastian Cox

If ploughing is bad, is digging too? When we plough or dig, we break the structure of the soil up. This seems harmless if we think of soil as chemistry - a measured mixture of minerals or nutrients, stirred together annually, like packed dried ingredients to which we just add water. But if we think of soil as biology - a network of connected living organisms - we realise that breaking it up is harmful to that complex ecosystem. Soil is more alive than you can imagine, if it is healthy. And you have to imagine it because you mostly cannot see it, which is perhaps why we’ve overlooked its value until now.

The Livingetc newsletters are your inside source for what’s shaping interiors now - and what’s next. Discover trend forecasts, smart style ideas, and curated shopping inspiration that brings design to life. Subscribe today and stay ahead of the curve.

The main engineer in this subterranean microscopic ecosystem is mycorrhizal fungi and its hyphae. These tiny strands of fungus work symbiotically to extend a plant’s root system, allowing it to reach moisture and nutrients from the soil which wouldn’t otherwise be available to the plant. This 450 million-year-old relationship allows a plant to reach up to 700 times more soil area that its roots alone, vastly increasing the plant’s health. It’s astonishing that we’re only really learning about this now, but soil hasn’t attracted the scientific interest and funding it deserves until recently. I’d guess that if our farming ancestors could have seen these organisms and their connection to plants, they wouldn’t have ploughed or dug their crops. Now that we have this knowledge, we would be wise to avoid chopping, forking and smashing our way through this incredible network if we can avoid it each spring. Of course, the mycorrhizae will grow back, particularly in already healthy soils, but why ask them to start from scratch each spring when you could just plug your seedlings into this developed network?

It’s worth noting that the reasons for not smashing up mycorrhizae extent beyond the ability of your plants to gain additional nutrients and water. The underground network they form teems with other invisible life; when we turn our soil we disturb billions of valuable organisms. Of course, we also break up the plants and their roots that form ‘ground cover’. When earth is bare, it dries to dust and blows away, a global problem of mind-boggling figures. This exposure of soil to sky also releases carbon stored there too. Astonishingly, our planet’s soils hold more carbon than all of the vegetation on earth. Every year atmospheric carbon levels increase by around 4 billion tonnes of CO2 due to human activity. Earth’s soils contain 1,500 billion tonnes of CO2. Incredibly, increasing soil carbon by 0.4% per year would balance our annual emissions. Jaw-dropping, right? Soil structure is as near as we get to a greenhouse gas silver bullet. It also significantly affects the earth’s ability to hold water, essential to both gardener and planet.

Leading no-dig gardener Charles Dowding shows the results of his low-effort methods on his Youtube channel and it’s astonishing. In one video he compares a conventional vegetable plot with a no-dig bed, and the difference in plant health and weed competition is huge. ‘Weeds thrive in disturbed soil’ he explains. His videos on Instagram are engaging too, he offers the idea that we feed the soil, not the plants - organisms like earthworms will drag the nutrients from cover crops and compost into the soil to make them available to plants, we don’t need to dig it down there.

I have recently learned to try to see the natural world through the lens of how it functions, and how it evolved to function. Generally, if our interactions with nature replicate or resonate with natural cycles, actions or events, they will cause less harm than if they don’t. When thinking about dig or no dig, there doesn’t seem to be any common natural occasion for soil to be turned from shin-deep. Rootling pigs only till the top few inches, it’s only tooled-up humans, thinking they know best, who go further.

In a natural landscape, nutrient-rich compost or dung aren’t dug in, but pulled down from the surface by soil-dwelling organisms, and plants are perfectly happy with this arrangement, having lived by it for millions of years. How hadn’t we noticed this before?

Dowding’s methods have been dismissed for years as left-field, but now we are gradually starting to realise the benefits to both our gardens and our planet of not digging - these no dig expert tips from Poppy Okotcha are a good place to start. I often wonder how long it'll be before Monty Don stows his fork on Gardener’s World as evangelically as he advocates peat-free compost and avoiding chemical interventions - both of which I wholeheartedly endorse, of course.

It’s perhaps an indictment of our propensity to say ‘well that’s just how it’s done’ that we still dig our gardens as the Victorians did. There is so much value in the ‘old ways’ because broadly they were a more ‘connected’ bunch, but we could be perpetuating nonsense if we don’t cross-reference traditions with modern knowledge. I think part of the problem in this instance is that we are too often distracted from observing nature by our now-unnecessary instinct to control it. For most of our existence, we’ve had to fight back wilderness and the danger it brought, so it’s understandable our desire to cut and cultivate is still strong. But now we are so far from this evolved existence, and so well-armed to destroy nature, we need to consciously let this urge go and accept new understanding from the simple observation of how nature works. Perhaps this is the very hardest thing about no-dig gardening.

I understand that gardening is based on the urge to intervene in nature, but perhaps the time we might have spent digging and forking each spring could be spent just watching and observing, instead. I for one will be keeping my fork in the shed this spring, and as it’s the season to be starting your veg patch too, please consider joining me.

Sebastian Cox is an award winning designer, whose work champions ancient techniques using materials found in British forests. An award winning maker, he has also written a manifesto for how we need to think differently about sustainability. He is a columnist for Homes and Gardens.